Women of the Past Paved Way for Female Scientists and Leaders of the Future to Thrive at Underwriters Laboratories

When Underwriters Laboratories was founded in 1894, only about 20% of adult American women worked outside the home, compared to 90% of men. Female scientists were rare, and female engineers were virtually nonexistent. In spite of this, women have always been key contributors to our organization’s mission to make the world a safer place. Like many women in the 20th century, our female employees had to fight to get a seat at the conference table and a bench in the laboratory. This Women’s History Month, we celebrate the women at Underwriters Laboratories who broke into the U.S. workforce, overcoming obstacles along the way. Through their perseverance and resilience, they paved the way for our current female scientists, employees, and leaders to thrive.

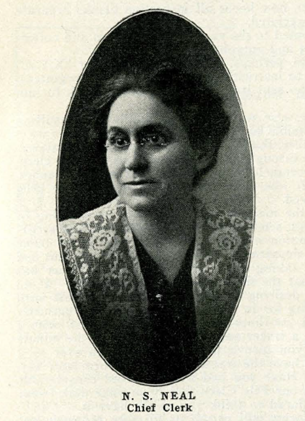

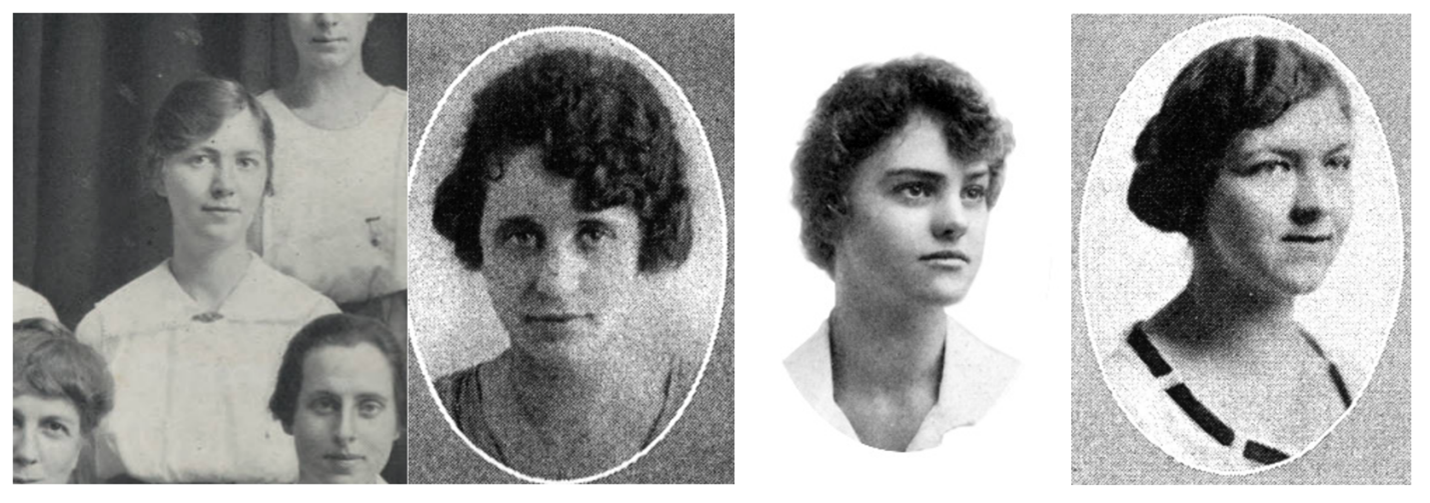

Nellie S. Neal, Underwriters Laboratories’ first female employee

Nellie S. Neal was was hired by Underwriters Laboratories’ founder, William Henry Merrill, Jr., around 1895 and worked at the organization until her retirement around 1935. She started off as Merrill’s secretary and was appointed chief clerk of the Chicago office in the early 1900s. She was known as an excellent writer. In 1908, Underwriters Laboratories’ Boston agent, Franklin Wentworth, was struggling to find a competent secretary. He wrote to Mr. Merrill and asked him to “send on Nellie Neal,” to which Mr. Merrill replied that “Miss Neal was well enough off where she was, thank you.” Clearly, Ms. Neal’s talents were well-respected and valued.

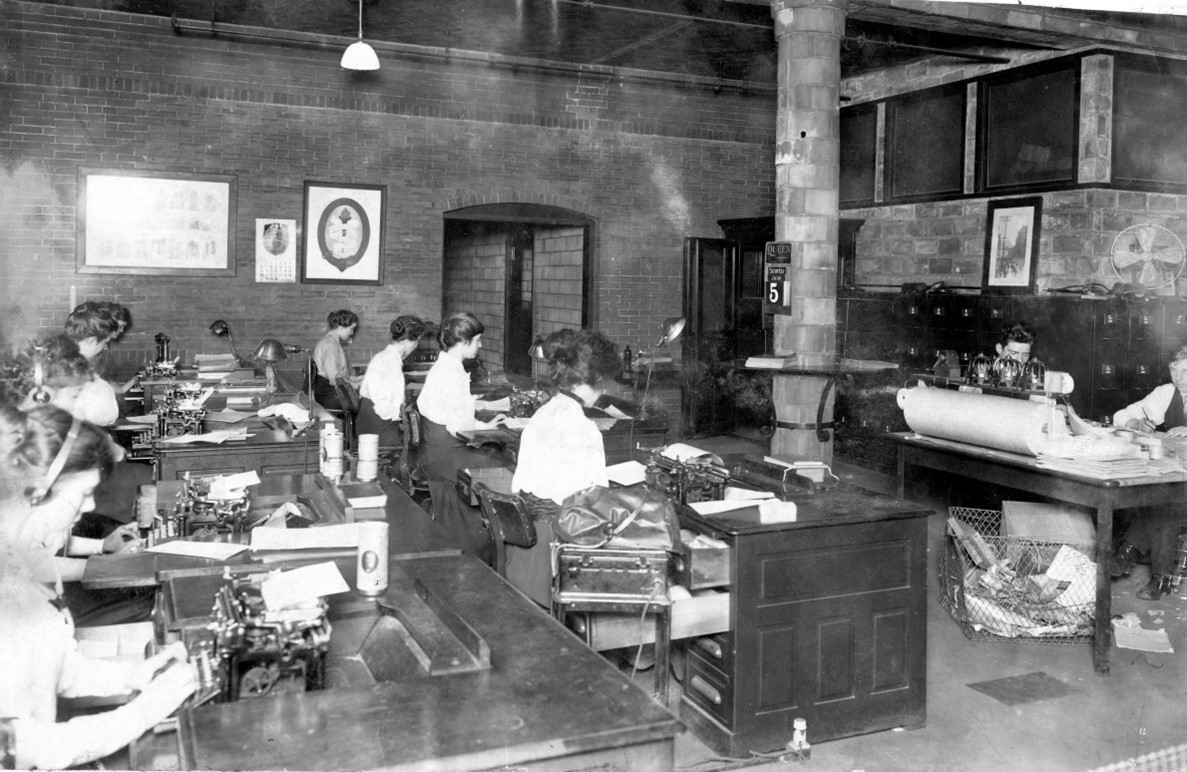

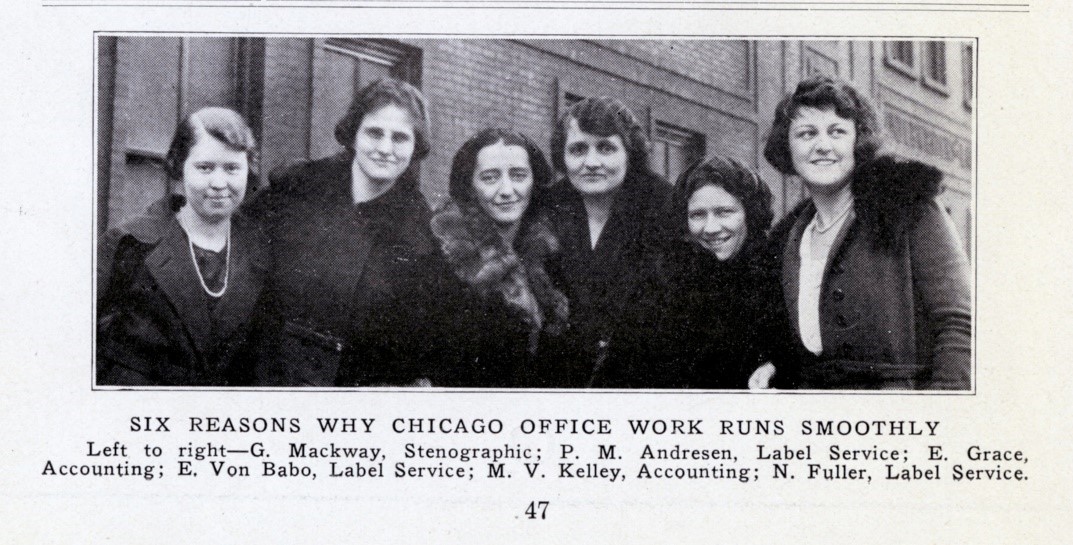

As was common in the early 1900s, the organization’s first female employees worked in stenographic and secretarial positions. Although they performed essential behind-the-scenes jobs, they did not have the opportunity to contribute to scientific research or engineering work, even if they expressed an interest in such a career path.

1919: Women chemists begin working in the laboratory

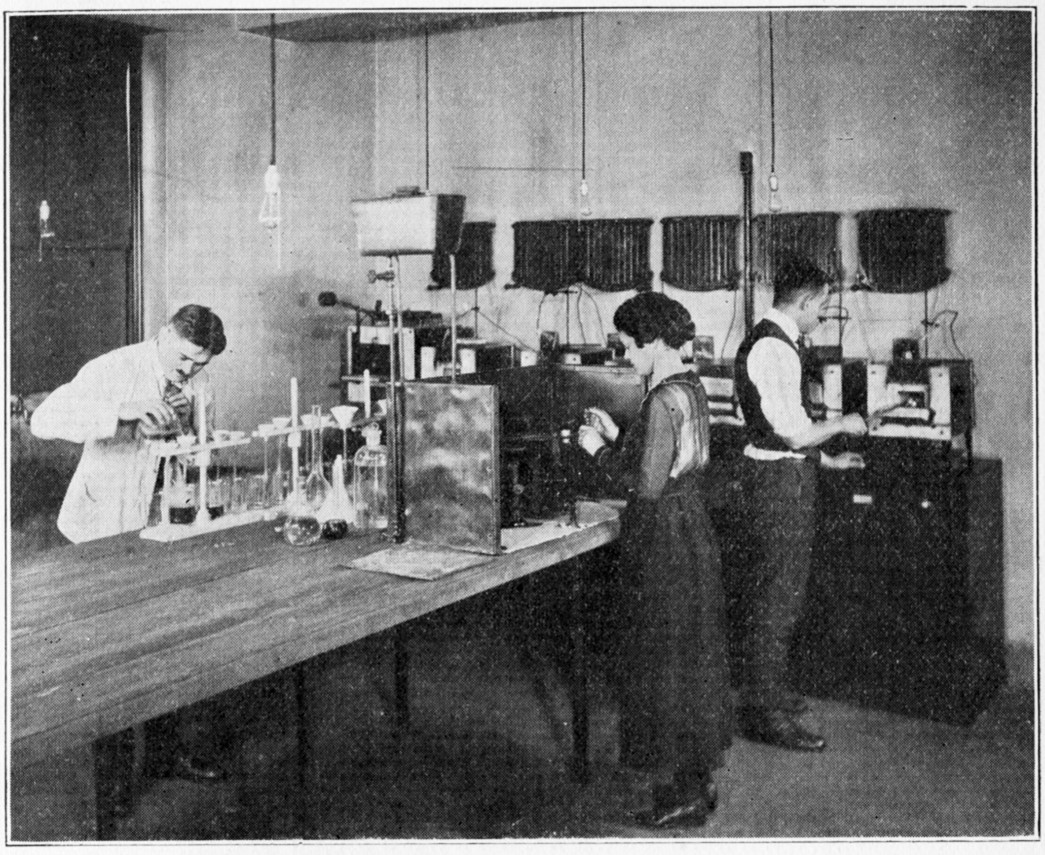

Their prospects changed in 1919 when Asa Nuckolls, head of the Chemical Department, began hiring female chemists. Women had entered the workforce in increasing numbers when men left to fight in World War I, and Progressive Era reformers and suffragists argued that women deserved equal rights. As a result, a growing number of young women graduated college with science degrees, eager for new opportunities in the fields of chemistry, biology, medicine, and more.

Ruth Custer, Genevieve Davidson, Louise Logie, and Helen Sellmer began working in the Chemistry Department in 1919 or 1920. Logie was the first woman to be photographed performing scientific work at Underwriters Laboratories. Despite these important strides forward, none of these women worked at the organization for more than a year or two. It is impossible to know why they left, but across the U.S., women struggled to maintain the workplace gains they had made during World War I. Men returning from war wanted their jobs back, and the 19th Amendment did not bring about the widespread changes for which the suffragists had fought. For example, Ruth Custer’s entry in the 1920 Purdue yearbook said the following: “Ruthie says that she expects to be juggling test tubes in a chemistry ‘lab’ five years hence, but we rather doubt it.”

Clearly, many people did not believe science was a viable long-term career for women as they were still expected to quit their jobs and stay home after they married. When the Great Depression hit in 1929 and jobs grew scarce, women’s chances of being hired as scientists grew even slimmer. Because of racist and xenophobic attitudes and laws, immigrants and women of color faced additional barriers if they wanted to break into scientific fields.

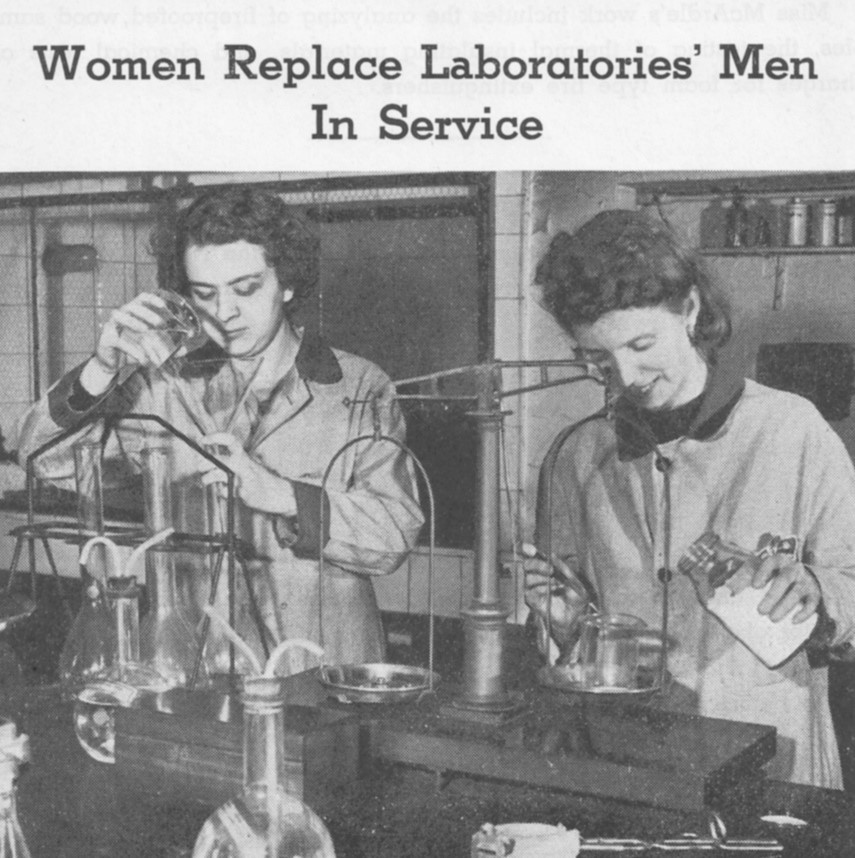

WWII: With men at war, women get more STEM opportunities

With more than a quarter of male engineers deployed in the Armed Forces, Underwriters Laboratories began hiring female engineering assistants and letting stenographers and secretaries perform lab work. These women kept the organization running through the difficult wartime years, supporting the mission to make sure American manufacturing operated safely despite widespread product shortages and rationing.

By the end of World War II, women in the U.S. had capably achieved business results in the workplace. No longer restricted to the fields of chemistry and biology and nursing, women became professional engineers in growing numbers.

1950 on: Society of Women Engineers founded, Underwriters Laboratories begins hiring women engineers

The Society of Women Engineers met for the first time in New Jersey in 1950, and Underwriters Laboratories began to hire women engineers around this time. Lois Bey, the first woman to graduate from the Illinois Institute of Technology with a chemical engineering degree, became Underwriters Laboratories’ first female engineer. Like many women of her time, Bey encountered sexism and pay disparity when she entered the engineering profession. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 made it illegal to pay women less than men for completing the same work, but American women in the workforce prior to this point had no real legal recourse if they were being underpaid.

Some women took a different route to become engineers, using their education in other scientific areas to launch an engineering career. For example, June Zimmerman and Lois Hwastecki were both hired as engineering assistants in 1943. Zimmerman graduated from Lake Forest College with a chemistry degree and began working for Underwriters Laboratories three weeks later. Hwastecki was still in college when she began working for the organization, eventually earning a B.S. in physics from DePaul University in 1951. They both stayed on after World War II ended, and in 1967, they were named associate managing engineers of the Casualty & Chemical Hazards Department.

Frances Newell, an agricultural engineer who was hired in 1954, ultimately became the managing engineer of the Standards Department, a title she held until she retired in 1984. When interviewed about being a female engineer, she offered the following advice to her fellow women in STEM: that they “should try hard, because whatever they do — good or bad — it is unlikely to go unnoticed.”

These women — the secretaries, the four female chemists, and the first female engineers — were all pioneers from different generations of American history, advocating for women simply by coming to work and doing their jobs each day. As Frances Newell indicated, female scientists faced increased scrutiny because they were women.

Since our founding, Underwriters Laboratories has made enormous strides forward in creating a diverse, inclusive, and equitable workplace. But there is always more work to be done. As we celebrate Women’s History Month, we honor the women who blazed the path, and we look toward our future as we strive to build a safer, more secure, and more sustainable world.

PUBLISHED

Tags