Safety Takes Flight: Looking Back at UL’s Aviation Department for National Aviation History Month

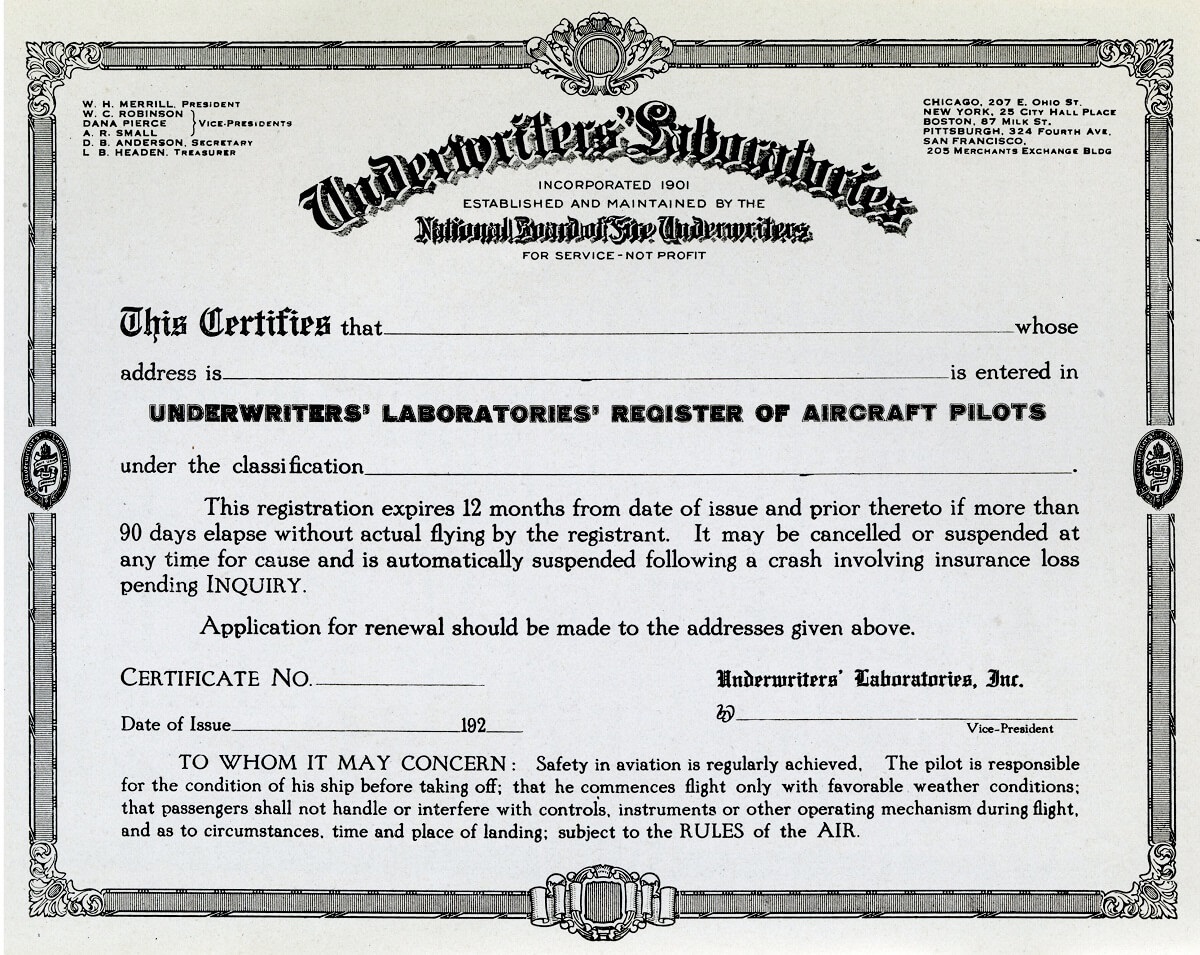

In honor of National Aviation History Month, we’re taking a look back at the early days of flight and how the UL enterprise — then known as the company Underwriters’ Laboratories (UL) — committed to safety in the air. Keep reading and learn how UL helped lay the foundation of aviation trust with the first U.S. registry of pilots and planes, plus an “airworthiness” certificate program.

Like many breakthrough industries, the first few years of flight resembled the wild west more than a planned community

Although Wilbur and Orville Wright made their first successful flights at Kitty Hawk in 1903, private and commercial aviation was slow to catch on in the early 20th century. It wasn’t until after World War I, when the Army had developed faster, safer, and more sophisticated aircraft, that private and commercial flight truly took off in the United States. By 1921, it was estimated that there were 1,200 civil pilots in the U.S.“An Analysis of Aircraft Accidents.” Aviation, September 26, 1921, 371-372.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) did not exist yet, however, so there was no agency to regulate civil flight. This caused a vast array of problems within the industry. Insurance companies were particularly affected because they had no method to underwrite the risks and hazards of flying.

UL helps lay the foundation of aviation trust

In 1920, the National Aircraft Underwriters Association (NAUA) turned to UL for help, knowing that our technical engineering expertise would be invaluable in addressing these issues. A few years earlier, UL had helped develop the methods for classifying automotive risks at the National Automobile Underwriters Conference. This gave UL the reputation as a leader in transportation safety.

In July 1920, the NAUA officially adopted a resolution “to avail itself of the services of Underwriters’ Laboratories in connection with the inspection of planes and the establishment of adequate manufacturing standards.”Summary of Underwriters’ Laboratories Aircraft Activities, 1958, Box 1, Folder 1, page 2, Water Damaged Collection, UL Archives, Northbrook, Illinois. Beginning in July 1921, all members of the NAUA agreed that any aircraft they insured against fire, theft, collision, stranding, and sinking had first to be registered by Underwriters’ Laboratories.“Underwriters Issue Pilot and Aircraft Registers.” Aviation, July 18, 1921, 78.

The safest pilot could not successfully fly an unsafe plane, and an unsafe pilot could not successfully fly a safe plane

Ultimately, it was decided that UL would register both planes and pilots. The booklet Rules of the Air, which UL published in August 1921, was the first set of rules for civilian aircraft in the United States.

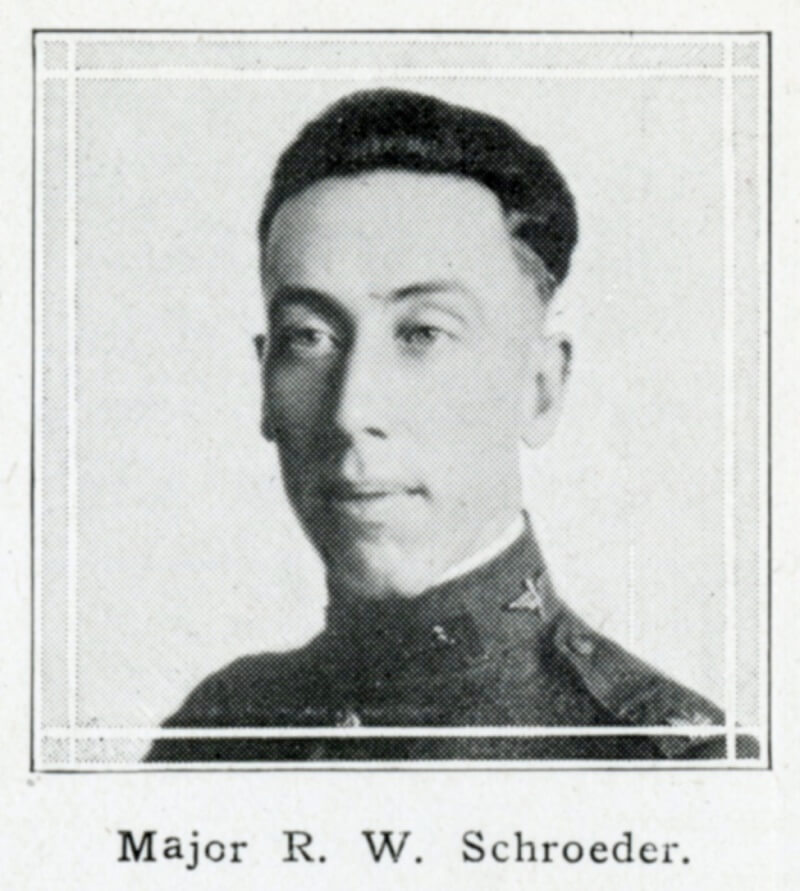

With UL’s Aviation Department officially in business by July 1, 1921, the first months were slow. Although many individuals and organizations wrote in to say they were intrigued by the program, few pilots presented themselves and their planes for registration. Business picked up in September, however, when Major R.W. “Shorty” Schroeder joined the staff.

Schroeder was an experienced aviator; he built gliders from 1908 to 1910, worked as an airplane mechanic from 1910 to 1913, served in the military overseas from 1917 to 1918, and eventually became the chief test pilot at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio.“The Tall Legacy of ‘Shorty’ Rudolph William Schroeder.” Director of Maintenance, 2015. He had set multiple world records for the highest altitude achieved in flight between 1918 and 1920 and was no stranger to the dangers of flying. He was also extremely well-known throughout the aviation industry. Many letters delivered to UL’s Aviation Department came addressed simply to “Shorty.”

Schroeder quickly got to work, and between 1921 and 1925, UL’s Aviation Department registered 47 pilots. The goal of this work was to keep unqualified fliers out of the skies and to ensure that pilots were not being granted insurance if they could not be trusted to handle an aircraft safely.

Previously, insurance companies had typically required pilots to fill out a “pilot’s statement” before flying an insured plane. However, pilots were not always honest when reporting on their flight history. There was no way to verify their statements, which meant that “many pilots endeavored to take advantage of the fact by increasing the actual number of hours flown, omitting to report accidents and in other ways changing their records to make them acceptable for insurance.”Martin, E.S. “Facts on Aircraft Insurance.” Aviation, January 2, 1922, 8-9.

To receive a UL pilot’s registration, on the other hand, applicants had to provide a comprehensive flight history. This included: how many hours they had flown; whether they flew privately or commercially; where they had learned to fly; if they had flown in the war; if they had any kind of stunt flying experience; and if they had ever had any accidents. They also had to have a medical examination that proved their eyes, heart, lungs, and other organs were in good working order. Finally, each applicant had to provide two references from people in the aviation industry. Schroeder would then write to each reference to make certain that the pilot in question was trustworthy, reliable, and experienced.

If the pilot met all the criteria, they received a registration that expired after 12 months. The registration would immediately be suspended in the case of an accident or crash.

Aircraft registry

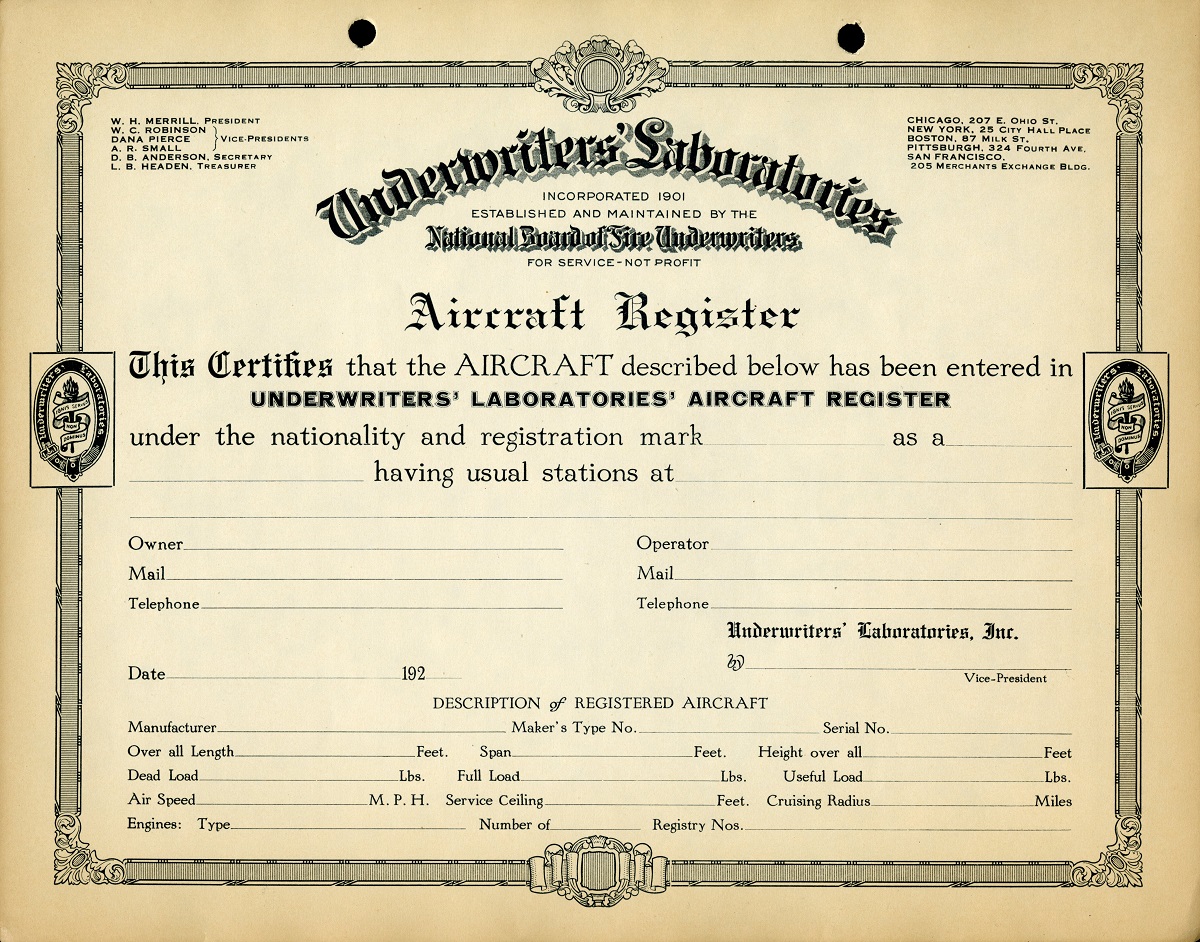

UL also registered 44 planes between 1921 and 1925. Each plane received a Certificate of Registry that covered the entire life of the plane, as well as a five-letter identification mark that was painted onto the plane itself. A plane whose mark began with “N” was owned by an American citizen and could be flown internationally. If the identification mark was underlined, it meant that the plane was intended for private use, rather than commercial flights.

Applicants for aircraft registration had to provide information about who owned the plane, who flew the plane, and who manufactured the plane. General specifications, such as the weight of the aircraft, the fuel capacity, the wingspan, the rated airspeed, and the types of instrumentation were also noted. Finally, the applicant had to pay a $5 fee to receive a place on the registry, as the registration covered the plane’s entire life and was not renewed every year.

Although no female pilots applied for a pilot’s registration, two female plane owners received UL registrations for their aircraft. Mrs. Tillie LaParle owned a Curtiss MF registered as N-ABCX, and Anna M. Parker owned a Curtiss JN-4D registered as N-ABKA.

The airworthiness certificate plan

During the end of 1921 and the beginning of 1922, UL also began crafting an Airworthiness Certificate Plan. This would take matters a step further than simply registering pilots and planes by actually delving into testing and certifying planes for safety.

For an aircraft to receive an airworthiness certificate, it had to be flown once a year and inspected for mechanical and structural soundness by a UL aviation engineer. Major Schroeder was based out of the Chicago office, so he hired 33 other inspectors from all over the country to provide national coverage of UL’s services.

The airworthiness testing was rigorous: After a thorough inspection, the UL aviation engineer was required to fill out a 17-page packet about the performance of various elements of the plane. Then the pilot had to take the aircraft up and fly it for the inspector, who was to remain on the ground for his own safety. The pilot had to track his speed, oil pressure, water temperature, and other factors while flying. If the plane met all the criteria, a temporary airworthiness certificate would be issued. After the report was processed, the official airworthiness certificate would be presented, valid for 12 months.

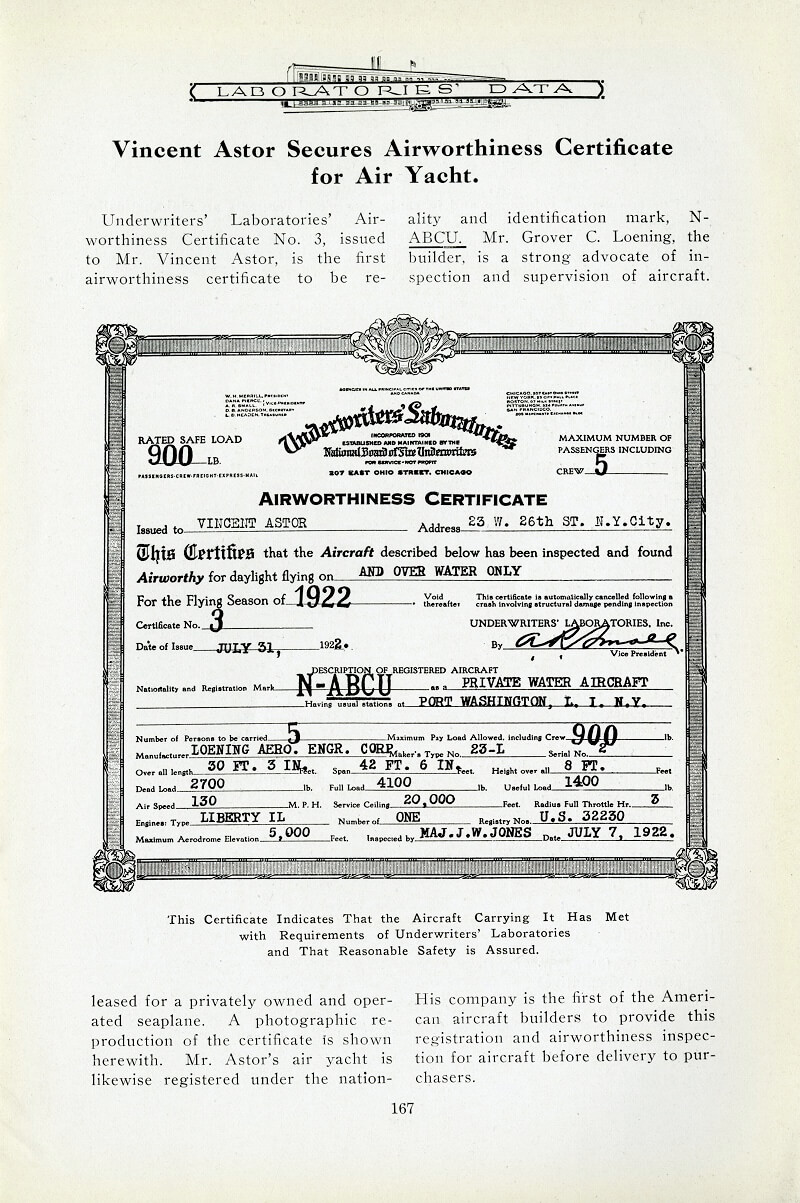

The airworthiness certificate program was not as successful as the pilot and aircraft registries: between 1922 and 1925, only 11 planes were certified for airworthiness. However, one of the most exciting episodes in the Aviation Department occurred because of the airworthiness program. In June 1922, A.P. Loening of the Loening Aeronautical Engineering Company wrote to Major Schroeder to say that his company was building two planes and he wanted to have them added to the aircraft registry. He also wanted to have one of them certified for airworthiness.

This request was normal enough, but the future owners of the Loening aircrafts were not: socialites Vincent Astor and Harold S. Vanderbilt, two of the most famous Americans of their time.

G.C. Loening of the Loening Aeronautical Engineering Company designed two special versions of his Model 23 air yacht for Astor and Vanderbilt. Then, Schroeder helped Loening register the two planes. He also contacted Major Junius W. Jones, UL’s resident aviation engineer in New York, to conduct airworthiness testing for Astor’s air yacht. Although Astor was the one to sign off on the paperwork, the air yacht was flown by a hired pilot, and not Astor himself.

Major Jones would later go on to become the air inspector of the Army Air Forces in 1943 and the air inspector of the U.S. Air Force in 1947. He inspected the aircraft, observed Astor’s pilot in flight, and reported back to Schroeder on July 26 that the “airworthiness temporary certificate has been issued.”Letter from Major J. W. Jones to R.W. Schroeder, July 26, 1922. Water Damaged Collection, Airworthiness Certificates, Folder 4, UL Archives, Northbrook, IL. Astor received his final airworthiness certificate on July 31, 1922, and UL received public recognition of the fact that aviation safety was important for everyone — whether the owner of a plane was a millionaire or just an everyday commercial pilot.

The end of the aviation department

UL’s Aviation Department lasted from 1921 to 1925 — just four brief years. By 1923, it was becoming clear no matter how well-structured UL’s aviation program was, the U.S. government was going to need to manage the industry for it to reach its full potential. Airways and airports needed to be built, and there needed to be consistent, enforceable air traffic laws throughout the nation.

R.W. Schroeder moved to Detroit in April 1925, taking on a new role with the Stout Metal Airplane Company at the Ford Air Post in Dearborn, Michigan.“Major R.W. Schroeder Resigns to Become Affiliated with the Ford Projects.” Laboratories’ Data, Vol. 6, No. 4, April 1925, 78. UL Archives. He worked in aviation for the rest of his life, eventually becoming the vice president of safety for United Airlines.“The Tall Legacy of ‘Shorty’ Rudolph William Schroeder.” Director of Maintenance, 2015.

In 1926, Congress passed the Federal Air Commerce Act, which charged the newly formed Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce with regulating U.S. aviation. The Aeronautics Branch would eventually grow into the FAA.

This doesn’t mean that UL’s early work in aviation was all for nothing, as UL pioneered the process of registering pilots and planes, put forth the first set of rules for the aviation industry, and inspected and tested civil planes for safety before the government did. The work of this department demonstrates UL’s lasting commitment to creating safe working and living environments for all people — whether on the ground or in the skies.

PUBLISHED