ULRI Awards Excellence in Youth Engineering at Discover Engineering’s Future City Competition

Institute for Research Experiences & Education Senior Education Specialist Jess Sparacino shares her perspective on participating in Discover Engineering’s Future City Competition, where she judged middle and high school teams’ research, ingenuity, and design for sustainable cities.

What kind of future is possible? That is the question Discover Engineering asks middle and high schoolers to answer each year during the annual Future City Competition.

One possible future is a world facing higher sea levels. The Earth is warming, ice is melting, and the ocean is thermally expanding. NOAA estimates that the sea level has risen at least 4 inches since 1993.

Rising seas pose risks to food security, freshwater supply, and critical infrastructure. How can we adapt our communities to not only recover, but recover better?

Last month, students from around the world convened in Washington, D.C. to present their answers to that big, bold question at Future City. They brought to-scale city models made of recycled materials. They prepared presentations about the engineering considerations that undergirded their designs and the project management strategies their teams employed to make their plans tangible.

The visionary designs these students shared were suitably audacious, and spirits were buoyant. This year’s theme was “Above the Current” — with students designing floating cities that meet residents’ health and safety needs. Our team at the Institute for Research Experiences & Education had the opportunity to act as judges and present a special award for “Excellence in Resilience Engineering.” It was no easy task: the student groups were overwhelmingly impressive. They had transformed research about potential futures into plans for responsive, adaptive communities.

Some cities were built as floating grids of modular hexagons because students had calculated that hexagonal geometry afforded structural stability to their buoyant landforms. Some cities incorporated artificial intelligence and Internet of Things technologies because students thought pattern recognition and swift data exchanges would expedite emergency response. Some cities were protected by responsive mobile breakwaters. Some cities were constructed with biorock and self-healing concrete.

No matter the tactics used, each student group brought innovation and creativity to the competition. One city was built in the shape of a whale, complete with a flapping fluke to propel the city away from danger while minimizing disruptions to marine life. One city distilled carbon from waste products into diamonds that could be used as a building material, data storage device, and exported good. One city was deliberately built near the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and devoted industry and research to cleaning up the patch, repurposing the garbage, and developing a circular economy.

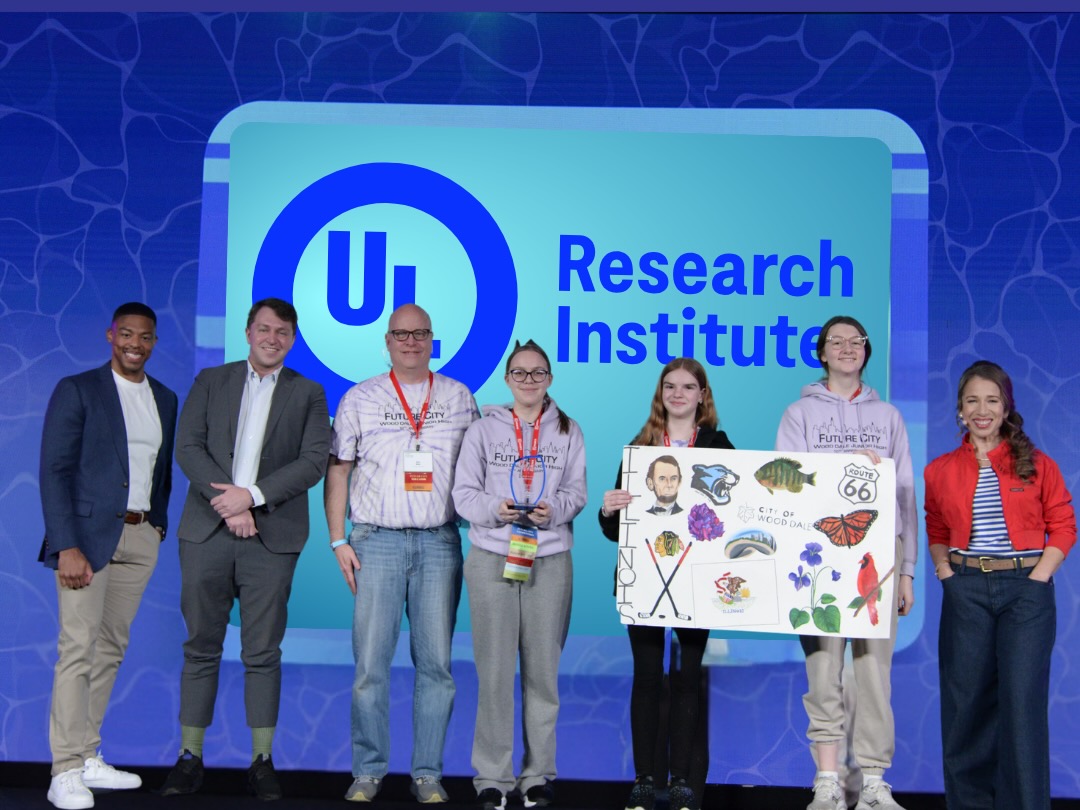

Ultimately, ULRI’s “Excellence in Resilience Engineering” award went to the team from Wood Dale Junior High School in Illinois. Their future city, Tupu, was built to float near the coast of present-day New Zealand. Their plan went beyond building a new city and included the transformation of the urban mainland back into a healthy wetland.

Wetlands have been identified as a crucial ecosystem for sequestering carbon and mitigating climate change, but today they are declining in quantity and quality. By prioritizing wetland remediation, the Wood Dale students learned from a global history of wetland destruction, planned to mitigate the risk of further sea level rise, and met the needs of their city’s residents — truly exemplifying transformative resilience.

Was this the only resilient answer to the challenge of potential sea level rise for future cities? Of course not. At the national competition alone, student teams presented dozens of plans, each one well-reasoned and unique.

By presenting their solutions, students at the Future City Competition demonstrated that immersive education about current real-world challenges prepares students to plan and prepare to better manage the challenges of today and tomorrow. Safety science education creates better possible futures.

Working toward the future of safety science means developing not only adaptable structures, but also adaptable professionals who can apply the principles of science, engineering, and project planning to create a safer, more sustainable world — just as these students did in the Future City Competition.

PUBLISHED